News of a lynching

May 26, 2010

Journalist Michael Herr wrote that Vietnam taught him ¨that you were as responsible for everything you saw as you were for everything you did. The problem is that you didn´t always know what you were seeing until later, maybe years later.¨

In January I saw a lynching. The facts are these. At 9 AM on a Friday morning I arrived at my affiliate university, Guatemala´s most exclusive school located in the sprawling, affluent suburbs on the city´s south side. While I was meeting with my advisor, three young men (including one boy) snuck over the barbed wire fence that surrounds the parking lot and robbed a student at gunpoint. By the time I exited the campus around 10:30 AM, word of the robbery had spread, and a crowd of 50 students had caught the men and begun to beat them. Although the campus police successfully extricated the suspects, students surrounded the traffic checkpoint where they were held and blocked an exit road, preventing additional police from entering the campus. Eventually, ambulances made it through, the purported assailants were taken to the hospital, and that was that, according to the three paragraph long account that appeared in newspapers the next day.

But what I saw, and remember, was this. As I walked out of the campus, through the closely guarded gates and under the razor wire, students from across the campus were running towards the parking lot. The spectacle was blocked by a bus, and so I didn´t see what was happening until I arrived at the bus stop. I for a moment I didn´t realize what was happening, I only saw a group of students dressed in carefully manicured American fashions, screaming and tearing at something. Then the police emerged from the crowd, holding the man with his hands handcuffed behind his back. His shirt had been ripped off his body, his nose looked broken, his face was bleeding. He face was taught with fury. The students followed. One, a boy in a black striped button up with gelled hair, jumped through the air, lifted his leg, and planted the sole of his shoe in the middle of the man´s naked back.

Too frequently, the violence I witnessed or heard accounts of in Guatemala City unfolded in close proximity to my comfortable daily routine. A wave of killings of police officers, possibly an attempt by organized crime to destabilize the center left government now in power, occurred on my route home from work and in my quiet Zone 2 neighborhood. And in the second week of March, my roommate and I were preparing dinner at 8 PM on a Tuesday night, when we heard the sounds of machine gun fire in the street outside our colonia. We learned later that a man in a pickup truck was shot by unknown assailants while driving his car. It was almost certainly a hit, as the assassins were probably waiting on top of a nearby house. The man was killed instantly, crashing into the wall that surrounded a nearby house. The next day I saw the cracks in the wall, now tilted and crumbling, revealing a pomegranate tree bearing unripe fruit within the courtyard.

But when I first heard the shots, I simply poured myself another glass of wine.

I haven´t written about it before because I didn´t know how to. This period was my most difficult in Guatemala City. I have never felt more alienated, more lost, more confused. Because it is easy to list off statistics that illustrate the prevalence of violence here, the lynchings, victims of femicide, and disappeared from the civil war, but it is much harder to reconcile these images of violence with the Guatemala I experience on a daily basis, a place with a culture defined by an unusual mix of deferential formality and ribald humor, where melodramatic love songs are the soundtrack of choice for burly bus drivers and children are cared for as treasures. How do such cruel cultures of violence emerge, and how is it possible that they are sustained? How can a place be so deeply traumatized that its people perpetuate the cycle of violence they have survived?

A month after I witnessed the lynching, I attended a ceremony that marked the beginning of the excavation of La Verbena, the public cemetery where unidentified bodies were dumped for decades and human rights advocates suspect the remains of the urban disappeared from the civil war can be found. After the various foreign diplomats from the embassies funding the dig gave their speeches, the group moved to the excavation site, a well several stories deep full of body bags. Family members of the disappeared were invited to name their loved ones, and to throw flowers into the grave. One by one, seemingly silent, stoic men and women, many now old, began to sob, screaming the names of their children and sisters, brothers and fathers. It was the sound of keening, grief so fresh and yet so old that it cannot be comprehended.

I would like to take responsibility for what I have seen, but I cannot even pretend that I have begun to understand it.

Welcome to the Zona

May 16, 2010

This week, I packed up my back packs, moved out of my Zone 2 apartment, and headed north, back to the Zona Reyna. I’m finished up my last few projects at P’s central offices in Guatemala City at the end of April, and so I’ll be spending the last three months of my Fulbright working with the literacy groups here, trying to get to the bottom of this Freire business. Even though working with teachers in communities was always my goal, those of you who have talked to me in the last month know that the move itself was a dramatic affair, resulting in many late night anxiety attacks, much buying of insect repellent, an array of last minute Q’eqchi’ learning attempts (more on that later), and even, occasionally, the utterance of a forbidden phrase: “What was I thinking?”

But the truth is that I knew very well why I wanted to move to an isolated village in the mountains. I would I would never really learn about bilingual education unless I immersed myself in the culture of a place where bilingualism profoundly shapes people’s daily lives. I’m excited to start visiting classes tomorrow, and to fill you in soon after. Until then, I will leave you with a newly discovered pearl of wisdom: roosters are excellent alarm clocks. If I had acquired one to go with my compost bin my junior year, I never, ever would have been late to my 9 AM stats lecture.

These pictures are from a Global Week of Action for Education event we organized at the end of this week in the Zona. I would tell you more, but my computer battery is about to die and I won’t be getting any more generator love until tomorrow. Plus, my new bike named Mercedes wants to go for a ride in the selva before the afternoon rains start.

Prisons and Education

May 8, 2010

I don’t always agree with the New York Times coverage of education, but they have the immigration and prison beats down. Both rank high on my list of “issues,” and as I start to consider my post-Fulbright options the idea of working for “school in prison” programs is particularly appealing. So I very much enjoyed reading this snapshot piece published today. It subtly illustrates the necessity of challenging many of our assumptions about such students. These particular men are persuasively articulate: the women we work with in the literacy groups here in Guatemala easily manipulate basic numeracy in their daily lives without necessarily knowing the names of numbers or how to add and subtract. Freire assumed that the oppressed are always afraid of freedom, that they need to be taught how to think and speak. But everyone has their own voice: the challenge is finding the space in which they can be heard.

The Trouble with Freire

May 7, 2010

In The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire includes a powerful example of how classroom dialogue can be not only inclusive but creative, generating new knowledge of the world. A group of Chilean workers were presented with a “generative image” of a drunken worker stumbling down the street: from the corner three teenagers watch with scorn. The drawing was meant to prompt a discussion on the consequences of alcoholism. Instead, the students defended the drunk. “He’s a poor worker like us,” they commented, “who works all week for his family but still doesn’t make enough to make ends meet and so drinks to forget.” The teenagers, they added, were simply lazy bums.

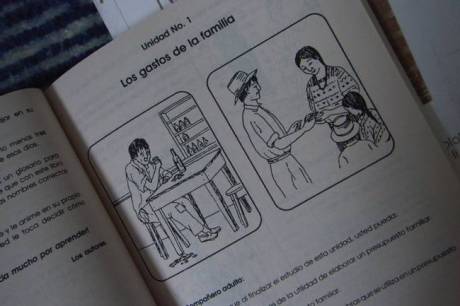

The very first unit in the CONALFA (state) “post-literacy” curriculum features a similar drawing. A man sits slumped at a table, his hand wrapped around a glass and a half empty bottle placed before him. His money is strewn on the table and has fallen on the floor. But the topic of the unit is not work, or wages, or masculinity, but rather the importance of maintaining a family budget: the image is juxtaposed with that of a “good” head of household, dutifully counting out the money allotted to his wife and children.

Emblematic of Latin America’s all-too-brief revolutionary moment, 40 years after its publication Pedagogy of the Oppressed has ceased to be radical. Rather, state institutions and their partner NGOs have adopted the methodology that Freire designed for social movements and community education projects. Freire himself participated in this process, working within the public education system in Sao Paolo in the 1980s. Depending on your political perspective (and how literally you like to interpret Freire), you can interpret this shift as a tremendous success or an outrageous act of co-optation.

But if the Freirean method really produces results- if it really empowers students to participate in the political process- such a debate might be a dead end. A more useful conversation, it seems to me, revolves around a related but distinct question, one I have asked before on this blog: Does Freire work? Does his methodology translate to different places, languages and contexts, and if so when, where and why does it work?

As part of my work for P, I completed an evaluation of last year’s literacy process that sought to answer this deceptively simple question. My deceptively simple answer? No, it doesn’t. Or at least it didn’t last year, in our 19 literacy groups spread across Guatemala. My initial analysis suggests that the reasons for this failure were more logistical than methodological, and I’m not ready to completely condemn the Freirean method. I’m moving to the Zona Reyna next week to work more closely with facilitators and students, and I think I’ll have clearer insight once I’m spending every day in literacy classes.

But my work on the evaluation did force me to confront some troublesome questions about the practical limitations of the Freirean approach when it is reduced to a primer. One would expect that if the methodology were successful- if it had really resulted in dialogue- both the facilitators and women would emphasize political and personal learning in their descriptions of the process. But one of the facilitators’ most common reactions to the “generative themes” was not the relevancy of the subject matter or the quality of the discussion, but rather the difficulty of teaching the words once they had been translated to the Mayan language. The students remarked that the process of forming new words out of “syllable families,” made learning more fun, but they hardly rhapsodized about the symbolic significance of the “whole word,” and many commented that writing even simple words was still difficult for them. And a significant number of participants interviewed said that learning to read was simply too hard for them, that perhaps their children could learn in a bilingual fashion, but that for them it was too late. Ensuring that the oppressed have the courage and confidence to claim their right to learn is the central goal of Freire: if the methodology can’t deliver on that, it simply isn’t achieving its objectives, and needs to be reformed.

(Another important point, which perhaps deserves its own blog entry, is the question of whether or not Freire is actually a good choice for bilingual educators, particularly when it comes to indigenous languages.)

Obviously, the implementation of the methodology was far from perfect. The Freirean methodology requires knowledgeable, confident teachers who know how to engage a class in dialogue. But our facilitators received limited training and support. Perhaps with better teaching and additional investment in childcare that might have enabled more women to attend regularly, it might have worked better.

Still, for all the trouble with Freire, I can’t help feel that a big part of the problem isn’t the idea of the methodology at all. The unintended consequence of Freire’s success- the institutionalization of his methodology across Latin America- is the codification of his complex vision of the classroom into just another set of workbooks, or, as this pointed brief argues, a “primer.” According to its authors at Action Aid, the Freirean approach has become exactly what Freire himself set out to reform, and in the process has lost something essential to his vision: a belief that true education consists in the reconsideration of one’s reality and the generation of new knowledge through dialogue. The Action Aid folks have hit on something important, including an interesting methodology I’m excited to tell you about it sometime soon.

So, you might ask, does Freire still matter? Yes, of course. He may not have provided us with a fool-proof methodology, but he does offer a set of guiding principles: he forces us to consider why we teach, what we teach and who we teach for. He asks us to take a hard look at our classrooms, to ensure that we are creating the kind of spaces that make true learning possible, and then to lift our eyes beyond them, asking what else our obligation to our students entails. Does the education we provide really serve our students? Does it challenge the order of things or confirm existing hierarchies?

The questions suggested by Freire are relevant not only in Latin America, but also in the United States, where renewed interest in education reform has not led to a deeper debate about poverty. In fact, such fervent interest in failing schools and bad teachers frequently obscures the complex relationship between public education and poverty. Education is universally presented as the solution to deeply entrenched racial and economic inequality. Yet surely our current “jobless recovery” makes it obvious that poverty is inevitable in a market system. Freire would challenge us to question these consequences, and to consider if education plays a role in justifying them, in excusing who “falls” to the bottom and who “climbs” to the top. We may no longer accept Freire’s Hegelian Marxism or his flawed methodology, but we should uphold his commitment to critique and his fervent belief in education as the practice of freedom.