Dinnertime in Guatemala, Breakfast in America

February 26, 2010

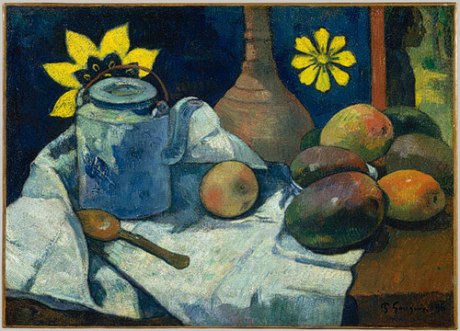

Bob Dylan and the some of the world’s best tortillas. How bad can Guatemala City really be when you’re having both for dinner?

Bob Dylan and the some of the world’s best tortillas. How bad can Guatemala City really be when you’re having both for dinner?

The only good thing I can say about the demise of my much-loved Gourmet is that it has allowed me to rediscover my first food-magazine-love, Saveur. A copy of the March issue on Los Angeles was one piece of highly valuable Estados-Unidos loot I picked up in the Atlanta airport, and includes a lyrical essay about a Guatemalan food vender named Lydia. You should read it too.

The only good thing I can say about the demise of my much-loved Gourmet is that it has allowed me to rediscover my first food-magazine-love, Saveur. A copy of the March issue on Los Angeles was one piece of highly valuable Estados-Unidos loot I picked up in the Atlanta airport, and includes a lyrical essay about a Guatemalan food vender named Lydia. You should read it too.

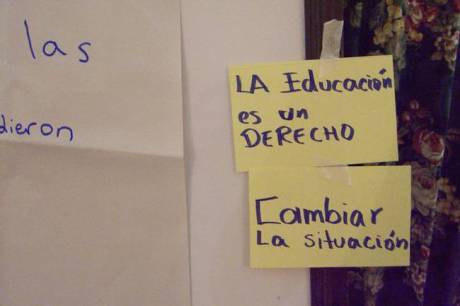

“La educación es un derecho”

February 26, 2010

I took a lightning trip to New York over the weekend, and my week in the Zona Reyna already seems like it happened a lifetime ago. But I have one more story I want to share with you .

One of the women in S was never officially enrolled in the class. Registering with CONALFA requires a government issued ID and a date of birth. But this participant was born in a different community, and moved far away with her husband: she doesn’t have her cedula and she doesn’t know her date of birth. That didn’t stop her from attending every class, or from taking the final evaluation using the name of a woman who withdrew in the first month.

When we distributed the certificados, one of my coworkers realized he had nothing to give her. He apologized, concerned that she would drop out now that she realized her accomplishment would never be legally recognized. In other communities, women were visibly distraught when they didn’t get their certificate or when they saw that their name was misspelled. (The CONALFA staff person did a really bad job filling them out.) In one community, where participants were already angry after learning that another literacy program run by a different NGO had given all their students chickens, confusion about certificates was almost the last straw.

But this woman seemed unconcerned. “No me importa, voy a seguir estudiando.” “It doesn’t matter, I’m going to keep studying,” she said. “But you won’t be getting a certificate, you’ll have no proof you completed your education,” my coworker explained. She responded calmly, without a trace of concern. “No me importa, voy a seguir.”

When education is seen as a right and not a privilege, everything changes.

Visitas

February 18, 2010

If you just look at the numbers, RS is a success story. Only three women withdrew from the process, and everyone reenrolled. Bu RS is the exception rather than the rule. Overall, about 30% of the women who began classes last June either didn’t finish or didn’t pass the final evaluation. CONALFA, the government illiteracy initiative that oversaw the evaluation and certification process, doesn’t have the resources to provide tutoring for students, so even women who miss the cutoff by just a few points are listed as retiradas.

Some communities had an especially high number of students who didn’t finish. In one town in the Zona Reyna, there were so many that the two facilitators suggested combining their remaining students, forming one group that would move onto the second year and another that would repeat the first. But P doesn’t have the funds for this plan, so instead we decided to offer one month of refuerzo so that the women would be able to continue.

Last Saturday, we squeezed into a van and headed out to S to visit each of the retiradas in their homes in an attempt to persuade them to reenroll. We split up: one of my coworkers went with N, our youngest facilitator, and I went, squelching and sliding in the mud, with M and C, the manager for all of P’s programs in the Zona Reyna who also, conveniently, speaks Q’eqchí.

At the first home we visited, the woman sat behind a sheet in her one-room house, her five children peeking out at us. “It’s hard for me,” she explained in Q’eqchí, as C translated. “And sometimes we don’t have corn or beans, and I have to go with my husband to the fields in the mountains.” After 20 minutes, she said she’d reconsider.

The second and third women we visited weren’t at home. The fourth family we visited runs a small store out of the front of their house, and the woman we were looking for was right behind the counter. But she told us we’d have to talk to her husband, and went off to call him. The man turned out to be an acquaintance of C’s from school who had worked both as a primary school teacher and as a facilitator for CONALFA. He led us to the back of their wood frame house, and sat us down on a bench. The woman brought us huge white tin mugs of coffee and then moved into the corner.

For the next 40 minutes, we proceeded to have a conversation about her, in front of her, but with someone else: her husband, the teacher and alfabetizador who, it became clear, was the reason she’d withdrawn.

“We have five children, she has too much work, she can’t leave them alone,” he repeated over and over, no matter what we said or how we said it. “But learning to read is work for your family as well,” we said. “But she’ll be able to help more in the store, she’ll be able to teach your children,” we said. C went so far as to subtly suggest that maybe her husband could help her with the children. I bit my tongue and managed not to deliver what would have surely been a feckless lecture on liberty and equality and sororité.

Finally, C turned to the woman, and asked her what she thought. She answered in Q’eqchi. Her husband was angry when she arrived home late from the meetings, delaying meals. “Better that you don’t continue,” he had told her. “I want her to continue,” he said when she was done, “but we have five children, she has too much work, she can’t leave them alone.”

These are the same reasons that almost every single woman who withdrew gave for her decision.

This is what Freire didn’t understand, what you can’t find in five chapters and 180 pages of Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Just changing the content and methods of literacy programs to reflect reality isn’t enough to overcome it, especially where women are concerned. Unless you can find a way to help women negotiate their gendered responsibilities, providing childcare and convincing men that women have a right to learn, it doesn’t matter how carefully you select your generative themes.

Thankfully, there is at least one man in S who is not machista. At the last house we visited, the woman explained that she had stopped attending classes after she fell ill. But now she felt better, and was interested in trying again. Her husband briefly came in to meet us. “Oh yes,” he said. “I want her to continue. How can she sign up?”

Please Sign Here

February 16, 2010

My very first student my freshman year of college was a little girl named A, and my very first task was to teach her to write her name. A hadn’t attended preschool, so didn’t know the alphabet. Over the course of my first difficult semester, we played with letter puzzles and shaving cream, flash cards and picture books as I struggled to find the right strategy to help her learn. When all else failed, I wrapped her fingers around the pencil and placed my hand over hers as we sketched out the five letters of her name.

Four years later and a few thousand miles away, I was once again struggling to help a student write her name. Except now I had not just one student but 40, and my pupils were not bouncy Kindergarteners but señoras bearing their babies in their shawls.

The purpose of our visit to the Zona Reyna was twofold: to make arrangements for the commencement of classes in March and to meet with the women who completed last year’s process. P has literacy groups in three communities, and we scheduled meetings with all the participants in each one. Owing to communication confusion and nonexistent public transportation, I didn’t make it to the first community. But on Friday everything went according to plan, and when we rolled into the community of R.S. at 9:15 AM, most of the women were waiting for us outside the school. It was somewhat unclear why classes were not in session, but the mayor soon arrived to unwrap the wire holding the door shut and everyone filed into the dusty two-room structure.

The meeting flew by, a cacophony of two languages, crying children and clattering desks. At the end, we began to distribute the certificates of completion to the participants, and asked them to line up to sign our attendance record. Afterwards, they were instructed to file across the room to sign another form affirming that they had received their certificates. It was my job to oversee this step, and we all assumed it would be fairly straightforward. After all, names were the first order of business when classes began last June.

But before I went to claim my corner, I watched one of the two facilitators ask a reluctant young women to sign her name on the attendance sheet. When the girl shied away, E helped her to hold the pencil, guiding her hand to form the letters of her name. Like many of the women in the group, this participant spoke no Spanish.

For the next hour and fifteen minutes, I stood in the midst of a crowd of women and small children, trying to persuade each one to sign their name. Many seemed hesitant but eventually copied their names from their certificates. It was a collaborative effort. One woman began translating my words into Q’eqchí: a young boy named C read out the letters for his mother and aunts. The women bent over the small desks, some nursing their children as they waited. Two young men watched from the window, occasionally laughing at the women. I wanted to tell them to stop, but I know exactly one word in Q’eqchí, and “Please stop being a machista pig and tell the women who raised you where to sign” is not it.

Teaching always involves the careful calibration of chaos and order. It requires complete awareness of the present moment and meticulous preparation. But sometimes the alchemic process of teaching surprises you, and a horrible situation suddenly crystallizes beautifully as teachers and students meet halfway.

In the end, all but two of the women wrote their own names, and everyone signed their first initials. The women were obviously embarrassed, ashamed, a fact they tried to laugh off. But it must have been terrifying for each of them to stand there, surrounded by their children and family and neighbors, all watching one another struggle to write each letter. In such circumstances, to try at all is a stunning act of courage.

After we gathered all the papers and the women moved to the church for another meeting, the mayor invited us to drink banana atole. As we sipped our drinks, we all agreed on the first activity for the next facilitator training: strategies for teaching names. If you know a good one, please let me know. We need all the help we can get.

Seven Days of Solitude

February 15, 2010

Yes, I am aware I have not posted for almost two whole weeks. I promised myself I would never let that happen (self-discipline is highly necessary in the post-collegiate world), but I failed. BUT I have a very, very good reason. I spent the last seven days in a town located twelve hours by bus from Guatemala City in the mountains of Quiché, a town with no electricity and no internet. The houses are still built out of wood, and there are no paved roads. If I were Gabriel Garcia Marquez, I would call it Macondo. But tragically I’m not, so I have to admit that the real name is Lancetillo. But if there was ever a place that illustrates the extreme solitude of underdevelopment, the Zona Reyna – the name of the region where Lancetillo is located- is it.

The Zona Reyna is three and half hours in a microbus from the municipality of Uspantán. Located in a valley in the mountains and composed of over 50 tiny communities, the Zone is named for the owner of a finca who originally controlled the area. Now very few of the people are tenants, but they still live in extreme poverty. Most survive as subsistence farmers, growing beans and corn. Cardamom is also grown as a cash crop. Last year was a good year: cardamom sold for $1.25 a pound. Usually, it sells for less than 25 cents.

Almost no one we met spoke Spanish. Even though the Zona Reyna is located in the province of Quiché, residents of the Zona Reyna speak Q’eqchí. Why? Like the neighboring Ixcan jungle, the ZR was settled during the Civil War by peasants who fled the violence in the bordering provinces of Alta and Baja Verapaz.

The unusual facade of Lancetillo's church, built to commemorate a priest who was killed by the military in 1981

The linguistic and geographic confusion means that both the official municipality- Uspantán- and the neighboring municipality of Cobán (in Alta Verapaz) claim they are not responsible to provide services to the region. Although there are schools, it would seem that classes are offered only sporadically. Consequently, P is already invested in education programs in the Zona Reyna, partnering with a school run by nuns in Lancetillo. Last year, my project set up five literacy groups in three communities, enrolling over 90 students. I visited two of these communities last week, and I have lots of stories to share. And I’ll be sharing them here, one a day, every day, until Friday.

On the Book Shelf: Black History Month

February 3, 2010

I’m sorry for abandoning my blog for a week! I was working on the most TERRIBLE transcribing project all weekend. Important life lesson: if you can’t really perform a given task in English, you will absolutely, positively, not be able to do it in Spanish.

I’m not done, but I decided to take a break from the horror of Express Scribe to honor the post-modern genius that is Black History Month. BHM was my exclusive curricular domain for two years, and a cause for much anticipation, planning and ransacking of the Teacher’s College library. Year one the theme was Harlem history, resulting in some of the greatest golden teaching moments of my career. Year two my friends weren’t quite up to the previous year’s reading list so we switched over to African-American artists and musicians.

The good news about teaching Black History month is that all sorts of former Black Power folks ultimately became children’s book authors, so a beautifully written, exquisitely illustrated body of work is waiting for you on the shelves of an urban library near you.

The bad news is that it is near impossible to find picture books about Black women that are up to the standard of Martin’s Big Words or Dizzy. There are a few, some listed below, but I have misgivings about many of them, especially for younger friends. Also, the publishing industry is run by white people, who provide the capital for an endless number of mediocre paperbacks about MLK but don’t see Malcolm X as elementary school material. They are wrong. To my knowledge, there is only one picture book in print about Malcolm X (by Walter Dean Myers), which becomes a problem when one wants to avoid forcing a liberal integrationist narrative onto one’s second graders. Hence my numero uno life goal: to write the Kindergarten-3rd grade Malcolm X picture book.

You may or may not be aware that February is also Dominican History Month. Whoever had that brilliant idea was probably the same person who picked the shortest month of the year to honor 400 years of deeply complex, contradictory history. AND he obviously never taught in Upper Manhattan, where half the students are Black and the other half are Dominican.

What’s a teacher to do? Extend Black History Month through the third week of March, which totally kills Woman’s History Month but whatever, my ladies knew they were amazing.

Harlem by Walter Dean Myers. This poem-picture book is a little bit too advanced for most of the under-9 set, but would be perfect for 5th graders. My second graders were extra-special, so we read it too, but didn’t go in too deep or try to explain all the tricky words. Instead, we focused on how Walter Dean Myers (who is definitely at the head of the African-American children’s literature pack) used his senses to describe his community, and talked about the things we “see, taste, touch, hear and feel” in Harlem. Brilliant Social Studies tie-in.

.

Uptown by Bryan Collier. We used this book in our “urban community” unit, so I couldn’t reuse it for Black History Month. And it killed me, just killed me, because this book makes me a little teary it’s so beautiful.

Martin’s Big Words by Bryan Collier. If you are a teacher, you are likely to have read this one to your students two weeks before Black History Month rolls around, so it is unlikely to make the cut. But it is unquestionably the best of the MLK picture books, and deserves a nod.

Henry’s Freedom Box by Kadir Nelson. This is not a book to be taught lightly. It deals with slavery head-on, recounting the famous story of a slave who literally shipped himself to freedom. But it is brilliantly well done, resonating with the kind of emotional power that characterizes the very best children’s literature. I suspect it might work well for advanced, mature 3rd graders, but buy it for yourself regardless.

A Wreath for Emmett Till by Marilyn Nelson. I wouldn’t touch this with a ten-foot pole in second-grade, but it is unquestionably a masterpiece of modern children’s literature. A heroic crown of sonnets – 15 linked poems- explore the brutal death of Emmett Till. Middle-school, this is all for you.

When Marian Sang by Pam Munoz Ryan. I like this book. But I don’t love it. I LOVE Amelia and Eleanor Go for a Ride. When Marian Sang is probably a good book to teach segregation in historical context, but I still found it necessary to do a lot of explaining, which awkwardly interrupted my read-aloud. And there is almost no dialogue, a no-no in the era of Mo Willems. But it is still a beautifully illustrated and elegantly written book, and one of the few picture-book biographies focuses on Black women. (Only Nikki Grimes’ Rosa has really made, deservedly but somewhat unsurprisingly, it into the “canon.”)

Tree of Hope by Amy Littlesugar. This mini-masterpiece deals with the kind of world historical events most people wouldn’t assume children can handle: the Great Depression, Orson Welles, Haiti. And yes, even my especially brilliant second graders probably didn’t know what the WPA was after we finished. But after we discussed the challenges facing the heroine, a bright young girl in Harlem whose father acts in Orson Welles’ famous Harlem production of Macbeth, one of my all time favorite students observed that the mother was tired and frustrated, because she had to work to support the family while her father followed his dream of acting, and that it wasn’t fair. Connections successfully made between art and life.

Dizzy by Jonah Winter. Filled with subtle humor and vivid language, Winter’s genius homage to the Jazz great reads like spoken word for children. We taught it with “Jazz art,” playing Gillespie’s best tunes and providing our students with paint and collage materials to interpret the sound visually. At the end of the year, one student wrote me a note: “Miss Holes, Thank you for reading us the Dizzy book.” Enough said.

.

Me and Uncle Romie by Claire Hartfield. If you, like me, want to cover all the art forms in your Black History Month unit, this is pretty much your only option on the visual art front. At least until somebody writes the Gordon Parks picture book. But don’t get me wrong: this isn’t Tree of Hope or anything, but it’s certainly an educational way to pass the half-hour prior to your collage activity. Hint: The Met has an absolutely fantastic Web site that explores one of Bearden’s most iconic works. http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/the_block/index_flash.html

Stitchin’ and Pullin’ A Gee’s Bend Quilt by Patricia McKissack. Skillfully weaving together the story of a quilt with the story of the community where it is made, Stitchin’ and Pullin’ is another beautiful book that is difficult to adapt to a lower-grade read aloud setting. I taught it last year by focusing on one poem, and trying to get my students to talk about how quilts can symbolize family and history. It didn’t quite work, but I am so thrilled that this book exists that would happily try again. The Patchwork Quilt, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, is another quilt picture book that focuses on an African-American family and would be worth teaching.

Tar Beach by Faith Ringgold. Tar Beach is not exactly a Black History Month book, but it is heartbreaking, magical and absolutely necessary. In a recent interview with the NY Times, Katherine Paterson, author of Bridge to Terabithia, was asked if she had ever considered writing for adults. “When people say, ‘Don’t you want to write for adults?’ I think, why would I want to write a book that would be remaindered in six weeks?” she answered. “My books have gone on and on, and my readers, if they love the book, they will read it and reread it. I have the best readers in the world.” Tar Beach is one of those books that goes on and on.